One popular theory has it that two rival processions tried to advance in opposite directions down an extremely narrow street, with neither being prepared to give way. Similarities with what is currently happening here in the Euro Area is, of course, entirely coincidental. What with the quantity of alcohol that people wandering the streets in the early hours during fiesta time would likely have consumed, and the fierce rivalry between the two "comparsas", the outcome is surely not that hard to foresee, or that worthwhile explaining. We can leave such details to the imagination of the reader.

But moving forward in time, and while again the versions of the story may differ, there seems to be little doubt that Spain's economy is in bad shape. Very bad shape. Such bad shape in fact that, according to Tobias Buck in a recent article in the Financial Times, it has left most of the countries population "bewildered". Bewildered, and increasingly desperate and despairing, or as blogger Matthew Bennett puts it dogged by the feeling that the modern Spain they know and love "is in danger". Indeed if we aren't all careful, the country could end up in a worse state than the one which befell that legendary rosario.

You know the Modern Spain you love is in danger.

Thankfully, you can still eat abundant amounts of tasty Spanish ham whilst drinking a decent Rioja, and the Spanish national football team is still beating all-comers at international level—a truly world class achievement—but in your heart of hearts, you know a cataclysmic future outcome is a plausible option for a Spanish society that is struggling to adapt to a new world economically, politically and constitutionally.

What happens to a society when tens or hundreds of thousands of its own citizens abandon the country to go and live and work abroad, with the approval of parents, government ministers and even the king? When record numbers of citizens—25%, nearly 6 million Spaniards—are unemployed, with no economic recovery or new jobs visible anywhere on the horizon? When the 12th largest economy in the world is ranked 136 for ease of starting a new business, behind Burundi, Afghanistan or Yemen?

What happens when Spain’s existing national institutions aren’t capable of offering all of its citizens and residents a prosperous existence, or when political leaders steadfastly refuse to listen to their voters’ repeated cries for change and prefer instead to repeatedly lie to the nation, ignoring their own electoral programmes?Put The Telescope To Your Blind Eye And You Will Surely See Recovery Ahoy!

For all the nay-saying to which those who watch the country passing thorough its agony are now subjected on an almost daily basis, there can be no denying one point - better days Spain has surely seen. Despite the constant and repeated assertions that great progress has been made with the reform programme, or that exports are doing just fine it's hard to see evidence for this in the ever longer lines of unemployed, or the now daily diet of home evictions to be seen in neighbourhood after neighbourhood. The number of reported green shoot sightings to which we have been subjected must now surely exceed the long term total accumulated for that other legendary beast, the Loch Ness monster. Yet this most terrestrial and long awaited of all resurrections has still not taken place.

But while the self-deluded continually claim to be envisioning signs of recovery, the data tell us another story. Almost every indicator we have points to deterioration, and the forward looking ones we have suggest there is worse to come.

The latest in the long line of examples I could cite comes to us in the shape of the third quarter GDP results, announced last week by the national statistics office. Between July and September the economy shrank by 0.3% quarter-on-quarter, or by 1.6% when compared with a year earlier, making for the fifth consecutive period of negative economic growth. This put the Spanish economy back at a level approximately 4.25% below the highpoint achieved in the first three months of 2008, just before it entered the great recession.

But, of course, all of this isn't over yet. At the start of last week the Spanish newspaper El Pais published details of leaked EU Commission forecasts for the country, showing that GDP is expected to decline by 1.5% in 2013, scarcely better than a 1.6 percent drop this year. Growth of 0.5% is then expected in 2014, and even if this result is eventually confirmed, what about 2015? Who is to say we won't be back to minus 0.5% again, or worse? Spain's economy won't be surging back to life again, the accumulated debt problems and continuing competitiveness issues virtually guarantee that, and only those who clutch hold of some kind of "but economies always recover, don't they" quasi religious type of fig leaf can summon the energy to convince themselves otherwise. The data and the analysis almost all point in another direction.

Yet, just like those historical reports that lie behind the rosario legend, this latest piece of economic data does inevitably allow for a plurality of alternative readings, and you can just glimpse a glass half full if what you really want to do is convince yourself that what is so obviously happening to the country actually isn't . Some will make a great deal of play of the fact that the rate of inter-quarterly contraction slowed when compared with the April through June period. Even the EU forecast can be used to this avail, since the annual rate of decline would seem to fall by one tenth of a percentage point next year. So thing are getting better!

Others will rejoin by pointing to the slew of other economic data which points to continuing deterioration, while yet others will argue that the fact the contraction wasn't deeper suggests the possibility that the austerity programme hasn't been all it is being made out to be, with the consequence that the deficit correction process is surely once more well off course. Indeed the EU and the IMF seem to now openly recognise this. Plus ça change!

At the end of the day, however, all of these interpretations miss what is surely the main point - Spain is and will continue to be stuck in depression, and not simply passing through a garden variety recession. Growth may be minus 0.3% one quarter and plus 0.3% the next. Frankly that doesn't change anything. Or at least not anything important. Without a more substantial set of growth restoring adjustments the economy will simply hover between growth and contraction for the rest of this decade, always assuming some major life-threatening event doesn't intervene first. The economy is broken, and there is no hidden hand at work on which to base expectations for an automatic fix. Recovery simply won't happen all by itself. That is to say, if someone somewhere doesn't do something to stop what looks set to happen happening, Spain and its economy can end up a lot worse off than even that famous rosario.

Let's look at some examples of what now seems to be more like a horror than an adventure story.

Credit, Houses and Jobs

The economic crisis afflicting Spain and its economy has many aspects, dimensions and layers, but through the fog three interconnected elements stand out clearly - the availability of credit, the stock and price of houses, and the levels of employment and unemployment. Whatever starting point you chose, the final outcome always turns out to be the same.

The country seems to be trapped in some sort of modern adaptation of the traditional children's game "ring a ring o'roses". There is a shortage of credit in Spain because the economy is losing jobs, causing the demand for and prices of homes to fall, leading banks to accumulate unwanted assets and clock-up a growing number of bad loans which in turn makes them reluctant to advance new credit due to the fear of have to assume even more losses. But we could equally say that the economy isn't creating jobs precisely because of this shortage of credit, and that the rising unemployment is affecting the housing market. Or, if we are still not satisfied we could put it like this: the fall in house prices is reducing demand for houses, and weakening household consumption (via the wealth effect - 75% of all household saving in Spain is held in the form of property). This drop in consumption is causing the economy to contract, with the result that it is constantly shedding jobs leading the banks to incur even more losses.

Whichever way you look at it these three interconnected components lie at the heart of the Spanish malaise. There will be no resolution of the Spanish "problem" without a turnaround in all these areas, and at one and the same time. Kick-starting the Spanish economy means inducing an expansion in the number of those employed, a freeing up in the credit gridlock and establishing a bottom in the downward march in house prices. At the present time none of these objectives are anywhere in sight. Unemployment is rising, and will continue to rise in 2013. People are leaving the country, credit is falling, and house prices have just had one of their biggest interannual drops since the crisis began. This dynamic produces a vicious circularity which puts the country at risk of enduring the same fate as all those generations of children who have participated in the aforementioned ritual, namely that the climax is reached when everyone cries A-tishoo! A-tishoo! and then lies down.

Water Water Everywhere, But Not A Drop To Drink

The question of credit flow is an especially complex one, since it is both cause and effect of the depression. Linear thinking will always have trouble with this kind of phenomenon. The banking system cannot freely supply credit since such a significant part of its balance sheet is "encumbered" with existing loans, some of which are already none performing. But there are many more which are in danger of becoming "troubled" if the crisis continues through the years ahead. Yet it is this very encumberment which virtually guarantees the crisis will continue. The loans in question are not only those made to property developers (many of these have in fact already been drastically written down). They are also syndicated loans to large companies, loans to small and medium enterprises, and loans to individuals for residential mortgages. As it is none of these portfolios are exactly going well, but the quality of the loans within them will continuously deteriorate for as long as the listless drift continues.

In addition, we need to remember that during the "good" years Spains banking system became considerably "overleveraged" - that is it gave an excessive number of loans in relation to the system's deposit base - in much the same way the Irish one did. So as well as working off distressed loans, the Spanish financial sector needs to reduce its leveraging which means (without a substantial increase in the volume of deposits) it has to cut back on lending. Naturally the kind of deposit flight Spain's banks saw in the first half of this year doesn't help matters.

So while the creation of the bad bank and the recapitalisation of the entire system will help clear some of the worst rubbish off the balance sheets, this doesn't necessarily mean that the clean up will lead to a flow of new credit, and indeed what has happened in Ireland (see chart below) tends to confirm this view. Irish banks handed over a large part of their distressed property assets to the bad bank NAMA, yet the interannual loan numbers continue to be in negative territory, just like the Spanish ones are.

To top it all, despite the fact that the country's banks had a net 378 billion Euros outstanding with the ECB in September credit is still not cheap.

Wholesale funding (where available) still comes at a hefty surcharge, and building the deposit base doesn't come cheap in a country where prices are rising at the rate of 3.5% a year. Typical fixed-term deposits now pay around 4%. Hence, according to the most recent ECB data (August) for lending rates to small and medium enterprises, German companies seeking a loan of €1million over a term of between one and five years typically pay something in the region of 3.8% – a record low for the Euro era – while their Spanish equivalent is paying 6.6%, the highest level since late 2008 when central banks cut rates after Lehman Brothers collapsed. So it isn't only wage costs that need to be reduced in Spain, capital costs need to come down to. This is naturally one of the objectives of Mario Draghi's OMT programme, but Mariano doesn't want to play ball, a strategy which may seem politically convenient but which comes at a high price for Spanish companies and those forming part of Spain's growing jobless mountain.

The second major issue facing Spain is how to stop the fall in property prices. Residential housing has seen falls now for almost 5 years, and prices are down around 30% according to real estate valuers TINSA, dropping by an annual 12.5% in October. Put another way, prices have fallen from something over 2000 euros a square metre, to around 1500. Spain's banks hold roughly 600 billion in home mortgages, and back of the envelope calculations suggest that once prices hit the 1,000 euros a square metre level the whole system (on aggregate) will be in negative equity - that is that homeowners will be standing on values in their property portfolio below the outstanding quantity owed in mortgage loans. At that point a critical moment will be reached, with the danger of implosion being much greater than "non negligible".

Spanish property prices have been being supported by a combination of three factors.

1) banks holding repossessed assets on their balance sheets

2) the illiquidity of the market, with very few transactions in new property taking place

3) a completely unfair distribution of risk between property developers (who can simply give back the keys) and those who bought the properties they built at the ludicrous prices they charged (who can't).

The nationalised banks are now set to move their "troubled assets" off balance sheet and into the newly created bad bank, Sareb. Although many questions still remain about the way Sareb will operate, its creation is unlikely to produce a turning point in the housing market, discounts may still not be sufficient to attract buyers in large numbers, and it is not clear how the mortgages those buyers who do appear will be financed.

Mortgages are not freely available in Spain, the volume of credit extended for house purchases is falling steadily year by year (see chart above) and attractively priced mortgages are normally only available to those buying properties on the balance sheet of the issuing bank. Those who seek mortgage finance for other property normally have to pay a hefty surcharge. Since Sareb will not be a bank, it will not have "own funds" with which to grant mortgages.

In the meantime Spain's unemployment continues to rise, hitting a record 25.8% in September. It is hard to say where this will peak, but the level looks certain to hit 27% in 2013. More importantly, simply getting the level back down to 20% again looks set to be a mammoth task, and one which is unlikely to be achieved this side of 2020. So many more years of pain certainly await the country.

One of the reasons the unemployment rate should peak reasonably soon is that people are now leaving the country in growing numbers. With 52.9% of the under 25 population who would like to work now unemployed a lot of young people are simply giving up and voting with their feet. According to data from the national statistics office, in June this year a net 20,000 people left the country. That may not sound like much, but it is a rate of one quarter of a million a year, or a million every four years. More worryingly the rate of outflow is on an accelerating trend (see chart below).

Natrually this wouldn't matter so much if the Euro Area was one single federal state, since health and pension costs would be shared across the region, so it wouldn't matter whether people were paying taxes or social security contributions in one place or in another. Indeed such movement would be a rather positive sign of the existence of a single labour market, and labour force flexibility. But the Euro Area isn't a single state, and contributions and costs aren't shared. So some countries risk becoming unsustainable.

Several years ago, and according to UN estimates Spain looked destined to become one of the oldest countries on the planet come the 2020s. That picture changed dramatically during the first decade of this century as some six million migrants came to live in Spain and the population shot up from 40 to 46 million in just a few years.

Before the arrival of the migrants Spain's population was virtually stationary. Really it is impossible to give any sort of precise forecast at this point of the Spanish population in 2020, or the rate of ageing, since the size of the population is so obviously path dependent on the evolution of the economy. It shot up as the economy was booming, and now it is falling back again as the country languishes in depression. It is almost a certainty that the population will continue to fall (births are also down) but how far and how fast depends very much on what happens in the job market.

This population exit has two important consequences. In the first place it reduces the future demand for housing, thus making it even more difficult to stabilise the market. And in the second place it means the pension's system, which is already becoming a significant drag on the fiscal deficit will continue to weigh ever more heavily on public finances, and will surely lead to ever more urgent and drastic modifications to the parameters in the country's pension system at some point in the future.

Exports Looking Good

Well, that is all obviously extraordinarily bad news. But Luis de Guindos (the country's economy minister) would retort, that some things are going well. Exports, for example, have put in a strong showing in 2012.

Not only that the goods trade deficit is reducing:

The current account has also improved substantially, and in fact went positive in July and August for the first time in many years.

The improvement in the current account is evidently good news, and it is even better news that it is accompanied by a rise in exports, and not just a fall in imports as consumption declines. But the disappointing reality here is that even despite these improvements Spain's economy is still contracting, contracting and running an 8% fiscal deficit. The reason for this is that Spain's export sector is still way too small for the work it has to do. I have been over these arguments time and time again, so I don't propose to go into them here and now. You can find the issue thoroughly discussed here (from June 2011), and here (from August 2010), and all I can say is that the arguments I use are just as valid today as they were then. I'm not sure how many others can say the same.

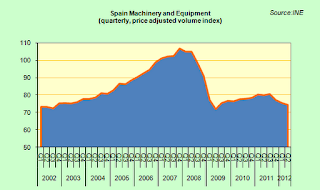

With the private sector deleveraging, and the government trying to reduce spending the only thing which can really grow to the economy is the export sector, but until that is bigger the impetus given to the economy won't be sufficient to offset the drag from the other two sectors, and the economy will hover around the zero growth mark. One sign that things were really getting better would be a surge in investment, which would be reflected in demand for capital goods, but as can be seen in the chart below this demand just isn't there.

Where Is The End Game?

The future of Spain is now very hard to see (so "que sera, sera"), and with it rests the future of the Euro. Interest rates on Spanish debt may well come down eventually if Mario Draghi starts the OMT bond buying programme, but as I argued in this post, intervention from the ECB alone isn't going to solve the Euro Area's underlying problems, only closer political union will be able to begin to address these, and that seems farther away than ever (or here and here). At the present time everything seems to be on hold, with Mariano Rajoy on the one hand reluctant to formally ask for a bailout, while Angela Merkel on the other is in no rush to do anything till after the German elections are over. Meanwhile those without work, and those about to be evicted from their homes just have to wait and see.

Even the deficit seems to no longer be a priority. Olli Rehn announced last week that Spain will not be asked to apply any additional austerity measures until at least the end of next year, despite the fact that everyone acknowledges the country will substantially miss its deficit targets both this year and next. The most recent EU Commission forecasts see an 8 per cent deficit this year and 6 per cent in 2013, but even these may be to generous now that the straps are off.

Obviously this loosening in the policy stance could be seen as positive, if you thought that measures taken over the next two or three years would return the country to sustainable growth, but the sad reality is that the vast majority of the structural reforms being enacted are only likely to have marginal effects on the countries overall economic performance, and the one that could, the labour market reform, was described by the ECB in its August bulletin as being too little coming too late. As the bank puts it, "the authorities finally approved in February 2012 a far-reaching and comprehensive labour market reform that could have proved very beneficial in avoiding labour shedding if it had been passed some years ago." As it is, the bank continues, "given the low level of competition, further significant reductions in unit labour costs and excess profit margins are particularly urgent....To achieve this, first, flexibility in the wage determination process has to be strengthened, for example, where relevant, by relaxing employment protection legislation, abolishing wage indexation schemes, lowering minimum wages and permitting wage bargaining at the firm level".

In other words, the country needs to initiate some sort of internal devaluation process to restore competitiveness, something I have and others been arguing for over several years now. But looking at the political landscape inside Spain after five years of unending crisis, this policy is extremely unlikely to be implemented as the political will just isn't there. The recent attempt by the Portuguese government to try something similar was over in a week on the back of strike and protests. Too much time has been lost, and too much weariness has set in. So the rot stays stuck in the wood, and one way or another we are on collision course.

But the biggest catch in the deficit loosening agenda is the impact this will have on Spain's debt trajectory. As I argued in this post, putting the submerged part of Spanish government debt on the table was always going to be a risky move, since the debt level could rise dangerously near the critical 100% of GDP mark, above which no one in this crisis has yet risen and come back to tell the tale.

Well next year it looks very probable we will now cross that particular threshold, and what's more Spain's deficit will continue adding to the level for several more years to come. In addition there are still unquantified risks in the financial sector. Despite all the lauding of Mario Draghi's OMT programme, it could well turn out that Germany backing off from the June agreement on mutualising the bank recapitalisation costs could in fact mark the critical turning point in the debt crisis. One of two groups of people are going to be bitterly disappointed after the coming German elections - German voters who are being promised they will not have to bear part of the costs of recapitalising the Euro Area's troubled economies, or investment funds who are being constantly reassured in the background that once the elections are over this is exactly what is going to happen.

So this year Spain's banks are going to be adequately capitalised, but what about in 2014, or 2015, or later if the crisis drags on and on? The new banking union may well be in place, but if the principal of not mutualising legacy debt problems is maintained, then it is hard to see how the losses on debt obligations which are currently being rolled over - like the large number of residential mortgage resets which are being used to avoid eviction - are going to be funded once the finally have to be recognised.

This week the tragedy of Spain's ongoing evictions drama has been in the news, (and here), and a new code of practice for evictions has been put in place by the government. But this is only scratching the surface. If, as seems probable, house prices continue to wend their way down then there really will be no way round the passing of some sort of new personal insolvency law to enable people to write down part of their mortgage, as we have seen in Ireland. The days of full recovery in Spain are numbered, since the social clamour, as in Ireland, will just become too great. Interestingly, ratings agency Moody's pointed out that in Ireland negative equity rather than unemployment was now becoming the main driver of mortgage default (and here) - and indeed they predicted that one in five Irish mortgages would be in default by 2013. This is interesting because the models used by Oliver Wyman and Roland Berger to stress test the Spanish banking system do not use negative equity as a parameter, relying mainly on unemployment levels and GDP movements for their default estimates. Spain's entire mortgage system is likely to fall into negative equity on aggregate within 2 or 3 years, meaning the capital requirements could then well be very different from the ones we are seeing now.

Then there are the regions. On the worst case scenario Spain could see a 20% drop in GDP as Catalonia exits stage left (elections are being held on the 28th - I have written extensively about this here, and the separatist case is put here), and if the Spanish government insists on carrying out its threat to veto continuing EU membership for any new state which might be created, the reality is that the rump country's debt level will surge to 125% of their remaining GDP, even assuming there aren't worse dislocation problems for the economy. Naturally one would assume that the Spanish government would negotiate rather than shoot themselves straight in the foot (typical prisoner's dilemma type stuff this), but you can't be sure, and maybe you should take them at their word. It doesn't matter it seems if the whole Euro project falls apart, if the Catalans vote to be independent they will not be permitted to remain in the EU.

Naturally, intransigence is seldom a good policy, and investors who want to take an interest in the issue might ask Spain government representatives who are locked in to their "total veto" and blocking strategy how, if they ever had to implement it, they intend to get their exports out to Europe. The lines in blue in the chart below show the national rail network, and those who know some geography will quickly see that there are only two connections with France, one through Catalonia and the other through the Basque country. I have no idea whether Catalonia will be in or out of Spain 5 years from now, but what I am pretty sure of is that if the Catalans left the Basques wouldn't be far behind.

So there we have it. What we have is a country where not only are people of working age leaving in growing numbers, whole regions may want to go. A country where deficit numbers have been flouted time and again while bank interventions have been consistently implemented using the principle of always try to do too little too late. The country suffers from what the ECB calls deep competitiveness problems, yet there is not a single proposal on the table at present which would do anything substantial to correct this.

The pension system is spiraling quickly into a substantial structural imbalance, yet the government will hear nothing of any deep long-lasting pension reform. I could go on and on. I would like to be optimistic, but five years of watching this train crash in slow motion have left me with the feeling that this one now has no solution. The country's political leaders just aren't up to the levels of complexity involved (see this excellent summary of some of the "matters arising" in this regard from César Molinas here, and Europe's leader not only drag their feet, they stick their heads in the sand at the same time. The exact details of how and when escape me, but this situation now has all the hallmarks of ending up in the same way as that legendary Rosario whose untimely demise gave the title to this post.

This post first appeared on my Roubini Global Economonitor Blog "Don't Shoot The Messenger".